While I may not think I subscribe to Selfie World, I do post the odd snap of self (and dog), features distorted by the lens, most often to say, “Hi, it’s a real person in here, and I laugh at my own jokes!”.

Some of us get a fright when we identify the hobbit in a group photo, the ceiling in a mirror at face height for your host. And trip over the disparity between the self that is us, and what we imagine we are less than. Self-acceptance is a thing best learnt early, and can be a struggle, but at any age we can learn something new about the cut of our kaleidoscope, and treasure it.

Acceptance of difference (and allowing ourself to be different) was a recent theme at a Salisbury Cathedral School assembly. Aimed to promote the “Don’t bully others who are different to your gang” approach. And to arm us against random unkind comments from the insecure that are part of life.

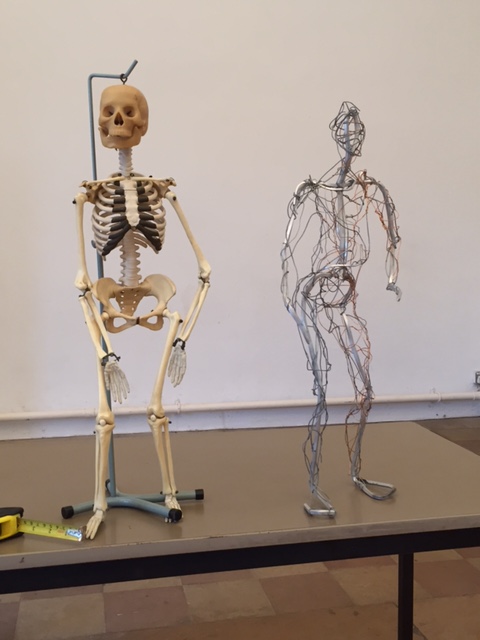

The wire selfie can be enlightening, empowering, and is a fun one to do with kids. Or with Salisbury District Hospital’s after work art club, and many others besides.

As Artist in Residence at Salisbury Cathedral School these last few weeks, that’s exactly what Years 7 and 8 were grappling with. By the cunning device of measuring the self in inches and creating the sculpture in centimetres, thus creating a, er, (insert fraction) scale model without doing any sums. I’m quite proud of that idea, and frequently use it with sculpture classes and in my own animal sculpture. Using both sides of the brain at once can be rather taxing. Best to use both sides of the tape measure.

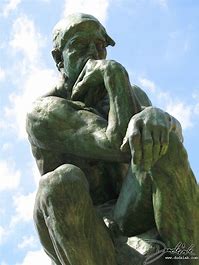

We start with looking at some interesting sculptures by The Greats. Sculptors I particularly admire for their capture of vitality include my hero Rodin, of course, Frink (who did what she did because Rodin had done what he did), Marini (funny, moving, mostly the man-horse combo) and Giacometti who’s main interest was the space around a person; so much so that the person themselves became compressed to a minimum by their own outline. There are lots more, but these are a good place to start.

We are looking at the individual, not the average or perfect, as often depicted in ancient Greek sculptures of athletic perfection, and again in Victorian art. Why is this person the only person who can hold this exact pose in this way? What is it that makes us say, “Wow!”? How can we make something that conveys that Wow?

Rodin was the master at showing us this. After his “too accurate, you must have cheated” Age of Bronze, his work became freer; more expressive. He slightly exaggerated, and altered scales. He often chose poses that, tried by the ordinary mortal, are extremely difficult to achieve, let alone hold for any length of time. Some poses require a body of particular proportions, such as Crouching Woman, above, and The Thinker, below. Have you tried holding that pose? Holding it and breathing at the same time? Go on, try it!

Some Rodin poses actually can’t be held, but are mid way between the two poses his model must have moved between. The Burghers of Calais were understandably a bit stressed as they were bundled off to be executed, but Jean d’Aire’s clenched opposing muscle groups aren’t technically possible. All-consuming cramp? However, this hugely add to the tension expressed. (These images are borrowed from a Bing search – mine are pre-digital, but I’ll scan them if I discover this isn’t the thing to do)

The Wire Selfie sessions can be a bit on the riotous side – people are moving around, measuring themselves and each other, sketching, wearing safety glasses and grappling with lengths of wire. I liken it to trying to train a room full of retriever puppies. A hoot!

“Can it have wings?” (Yes – great idea!)

Skinny slight lad in a group of multiply expelled kids (not SCS!): “Does it have to be life like?”. (Keep the skeleton lifelike, then build up how you like). Huge muscles ensued.

“Why’s yours bigger than mine?” Petite girl to strapping lad in another excluded group.

How best to understand our place in the ecology of world – our negative shape? Learning from Rob MacFarlane’s fabulous “The Lost Words”, the shape that isn’t there can be just as powerful as the shapes that are. Notable by their absence, their silhouette, their habitat changing without their influence. He refers to words of the natural world that are falling out of our children’s dictionaries, being replaced by digital age words. Those of us who had a gloriously muddy, creative childhood have a huge resource to draw on. We are shocked at this news, and fight to keep children’s delight in nature alive. And ours.

I had a conversation with a fellow sculptor recently, about the joy of seeing patterns in the bubbles in the bath. I saw some Galapagos islands in mine, and the profile of a friend. He saw something equally relevant in his. “What joy!”, we agreed. How lucky we are to see a world in our bath! Sometimes this shape recognition is overwhelming, and on a countryside walk I see umbrella handles and huge grey spiders disappearing over a river bank (swan necks and cygnets), or bright flat geometric shapes (a reflected bridge with sunlit bracken, jagged trees and another swan). Here lies Alice in Wonderland. And we see people everywhere. Animals do it too, shying at shadows and snowmen.

Mary Oliver puts it beautifully, in her poem, Wild Geese:

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

In portrait sculpture, the sculptor must have a good understanding of their own appearance so that doesn’t overwhelm their portrait of the model. You will sneak in, try as you might, but the end piece should aim to have only a pinch of its maker. Frink portraits are easily identifiable, possessing a recognisable element of her strong handsome features and bearing. Left to our own devices, we are battling an instinct to create a balloon-shaped head with our own features, and maybe hair similar to the model’s. Its easier if you don’t assume you know what you’re looking at.

80% look; 20% do, is a useful maxim of Rodin’s. Measure at the beginning, but looking is your most powerful weapon. Looking and seeing *. Understand the bones and muscles. Get your model to move and tell them jokes. Put your tools down and look at the model and your work from a distance. “Simplify!”, my tutor, Harry Everington, at the Frink School of Figurative Sculpture used to say. Again and again. Look for the strongest geometric shapes, and the patterns between them.

As a tutor myself, I tend to make a piece alongside my students. Going through the layers of looking and sharing discoveries is more inspiring than pure criticism. This one of Reme, a friend’s niece, is nearly there. Chin needs reducing (mine is rather huge), and eyebrows need to come down a bit (perhaps I was peering, specless). Why does this person look like that? How can you tell what they are like as a person by looking at them? Book? Cover? It’s a mystery, and that is what keeps me enthralled by the process.

Now, who’ld like to sit for my next portrait class at Salisbury Arts Centre?

*Another Mary Oliver poem from her book, Why I Wake Early: Look and See

Wish I could be your student. . Talk about inspiration.

May I send it to other people?

Xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, of course, Mum. I’m your student, any road! Xx

LikeLike

Thank You Lot

Such an interesting and thought provoking read

(Think your selfie ratio is 1:2.5 isn’t it? You are the maths boffin)

Let’s go to Giacometti on 22nd ?xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mat – yes, let’s do that xx

LikeLike