All all alone lone the wide wide sea…. Well, apart from four fellow Salty Moretons, resting below decks, Counting Stars – a companionable catamaran with a family of American sailors, and a fair amount of commercial shipping. With his Ryme of the Ancient Mariner, Coleridge gives us an epic to remember in snatches and piece together in the wee hours. On night watches unfamiliar stars shine, layer upon layer. Is that the Southern Cross? We’re doing Big Bang Theory in Boat School, Stella and Fin soaking up information and drawing colourful timelines to adorn cabin walls. (Turns out to be a very fitting moment, Stephen Hawking passing away as we sail and learn.) In Philip Pullman’s Book of Dust, a nun doesn’t have a problem squaring the 13 billion years since the Big Bang with creation theory; days were longer then. Perhaps he’s…. No, never mind.

Listening to the stars, I strain to hear the chiming music of the spheres, as described so beautifully in Laurens van der Post’s A Story Like the Wind. “A story is like the wind,” he says, “it comes from a far off place and we feel it”. The first book to make me weep at the end as I could not read it again for the first time, though I’ve read it many times since. This is a book to teach us to live in tune with nature, if ever there was one. We plan to put our sweat where our sanctimoniocity (did I make that up?) is and join a couple of Galapagos projects that are supported by the Galapagos Conservation Trust to educate about the evils of single-use plastic. If we use it, we eat it, eventually – reduce, reuse, recycle. We forget to examine the stomach contents of the rainbow-clad bonito tuna we catch and eat, trusting that although we caught it and it’s fellow between Panama and the Las Perlas islands, both of which are strewn with non-biodegradable trash, that it is as unspoiled as the Galápagos Islands 800 miles ahead of us.

After a while a red full moon rises and banishes all but the nearest million or billion (mas o menos) stars.

A ditty by T.E.Hulme, whose imagery springs to mind on these occasions:

Above the quiet dock in midnight,

Tangled in the tall mast’s corded height,

Hangs the moon. What seemed so far away

Is but a child’s balloon, forgotten after play.

A following wind heaps Prussian blue water in flopping, sighing crests; shadows mistaken for dolphins. Definitely not for sea monsters, no. Brian the wind vane keeps us on track. (Good Vibrations, Beach Boys, Brian Williams, geddit?). I check and recheck the AIS, relieved that we can track the distant lights as they materialise into enormous vessels. We can see what they are, their course and speed, and together with the hand-bearing compass lit by a head torch set to red, ensure we can safely slip between them as they round the small Pacific island of Malpelo.

Pre-passage showers and clean hair wear off by day two, hair twisting into spaghetti in the salty wind. Wash on day three. Noodles and doodles – draw a small squiggle (two lines and a dot) and your playmate squiggles more to make a picture. Hours of fun! I later discovered it works in Spanish too.

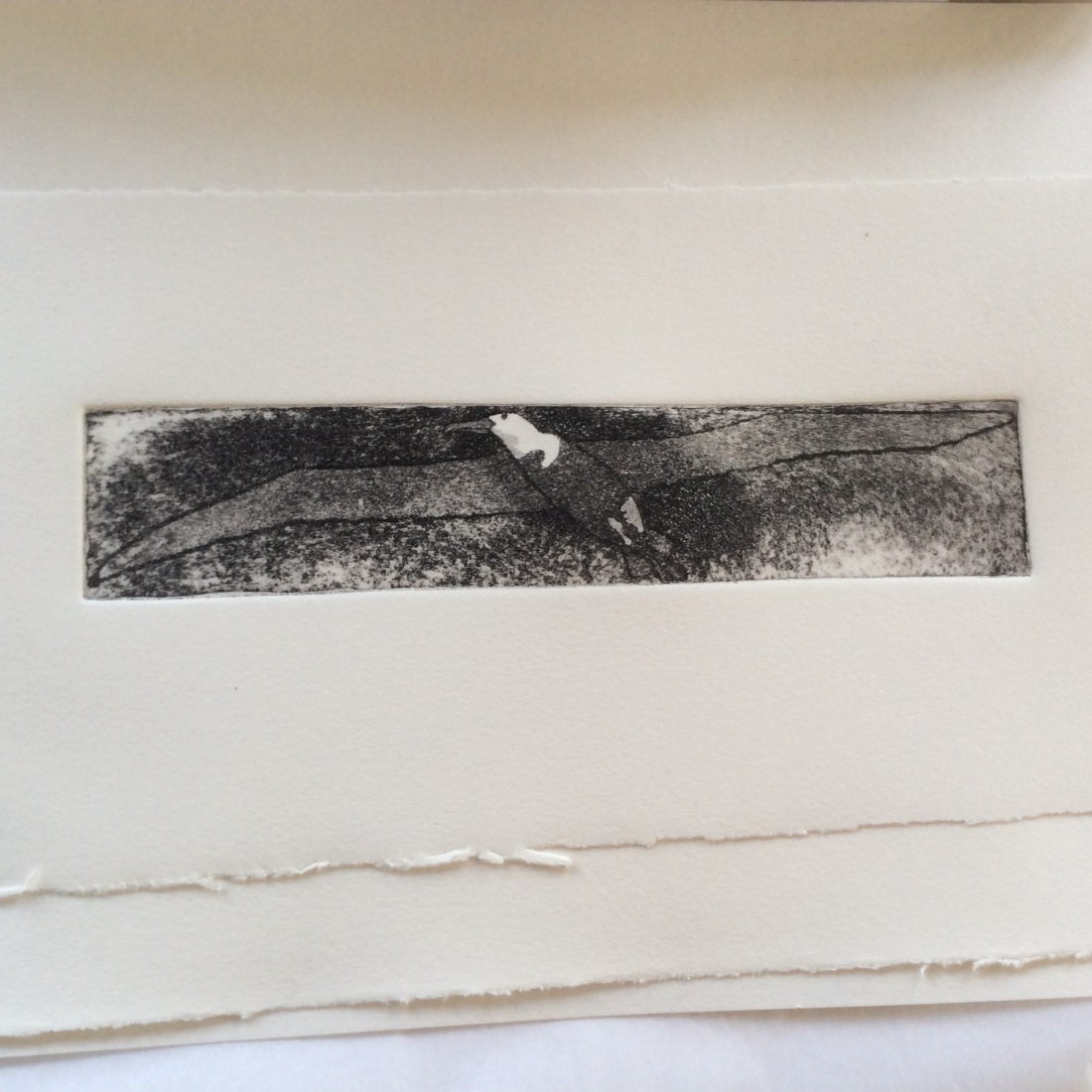

Night again with glittering sparkles of phosphorescence and bright trenches ploughed into the sea under us.

Horizon light of Flying Fish, an American father and daughter team, seen eight miles behind us as the shrinking moon struggles up through a wedge of grey cloud.

Francis Thompson’s Arab Love Song:

The hunched camels of the night trouble the bright and silver waters of the moon.

The maiden of the morn will soon through heaven stray and sing, star-gathering.

Now while the dark about our loves is strewn,

Light of my dark, blood of my heart, O come!

And night will catch her breath up and be dumb.

…The rest of the familiar poem flows easily.

Feet get harder, fingertips softer. The continuous glucose monitoring device comes into its own on night watches, when disrupted sleep patterns can cause havoc. Kind skipper gives me the first watch to minimise disruption. After a bit of nimble tweaking, the sensor is secured into place on my arm with a wound dressing to protect it from bashes. The previous one, tried out at home, lasted only three days before an unnoticed bash broke it. This one does as it should, lasting a full fortnight, in and out of salt water. It is brilliant – saves the fingers too.

Food is cooked in order of shelf life and signs of rot. We shall end up with squash, water melon and pineapple surprise. The carrots last an unexpectedly long time, individually wrapped in foil with the ends free. The cruising boat network is alive with such handy tips.

William Beebe’s enthusiasm for this journey in his Galapagos: World’s End, is a refreshing bucketful. He set off from New York in 1923 with a shipful of scientist, lawyer, artist and several other bods of specific skill, for a rollicking adventure, enticingly described, bringing in philosophy and literary quotes as well as beautiful and precise illustrations and sharply observed science. My kinda guy.

A school of a dozen pilot whales investigate us, approaching, falling back to discuss their findings, bounding forwards again, until, satisfied, they head off.

A brown common booby from the mainland sails around and around the boat, head tipped to one side in curiosity. A handful of lone and pairs of masked boobies sit on the sea and watch us go by. Could these be Galapaguenos already? Anna and Fin meet a pair of red-footed boobies, stopping at dawn for a brief visit. Definitely a vanguard.

Follow the moon on the water. So the fortune teller told the carousel pony as he left the circus. Anyone else read that book? Possibly written around the 1930s, read with Oldgran, but I can’t remember who it was by or what called.

Waking up with full sympathy for Kafka’s Gregor, incapable of bending in the middle, flailing beetle limbs, after a few hours wedged in my bunk trying not to roll to the ocean’s breath.

Crossing the equator is a serious business. A feat I achieved aboard the sailing tour ship Cachalote four years ago, along with tots of rum and a group photo shoot with dreadful yellow T-shirts. This means I am a shellback and the rest of the crew, being new to it, are polywogs, and I get to be Neptune/Poseidon this time, wearing a foil crown and brandishing a trident. According to U.S. naval tradition, there’s a way to do these things, involving Neptune accusing, humiliating and initiating newbies. We concoct a family-friendly version, suitable for after dark.

“I am Neptune, I am Poseidon, smelling of seaweed by any name!”

“How should we address you?”

“Darling!”

Punishment – sea water over head, spaghetti over head (raw egg for the worst crime)

“Safely sail!

Love the whale!

Tell your tale!”

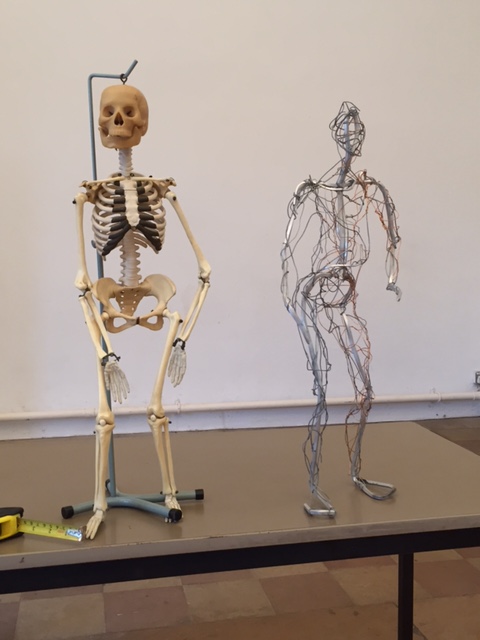

Welcome to the order of Neptune – adorn with wire sea-animal and cowrie medal.

Libation – give him a tot of rum, and (oh yes!) rum and juice for us too.

Offering – pineapple surprise upside down cake (with six spoons – definitely too much for Neptune to manage on his own), mermaid drawing, precious shells, poem and medal.

My watch after all that is a long one. I stand on the deck, clipped to a shroud and balancing to stay alert, or at least, awake. I think of core strength and imagine my nasty midriff getting the message. I stay there for an extra hour, watching the sea and sky and taking the chance to give the skipper an extra hour’s sleep, and myself extra Pilates.

After five and a half days of spinnaker run (goose-winged at night) we snuggle into Baquerizo Moreno harbour, San Cristobal, the first Galapagos Island visited by Charles Darwin that September in 1835 on his momentous journey. Had The Beagle left the island to starboard they would have found plentiful fresh water falling over a cliff, flowing down from El Junco crater, 700m above. However, he left it to port, landing at Cerro Brujo. No fresh water to be had. Back to now and, anchored and still salty, we drink another libation to ourselves and a kind Neptune, and sleep a long sleep and a sweet dream, the long trick over.

Too few hours later we awake to underwater sealion barking (“Urfbubble, urfbubble, urfbubble!), soon followed by the first of a long procession of officials to inspect our fitness to be here. A big ketch with a weedy bottom is turfed out early – our chances of approval improve. Maybe Ronald the plastic duck swings it, together with many weeks of preparation by Patrick and Anna, a spotless boat and our crew uniform of booby-blue toenails.

Our landings and swimmings are another tale. The next night passage – to the largest Galapagos island of Isabela – is eighty miles and a single night, motoring over a silky glassy sea in a pool of phosphorescence. Glistening shapes streak towards the boat, criss-cross and speed away, unidentified. The skipper sees a dolphin leap right out of the water in a midnight firework display. Big white handkerchiefs, or maybe the nocturnal swallow-tailed gulls flap around the forestay. Espanola island, invisible to our south, is still empty of the albatross at this time of year, but this gull nests there too. Tour boats pass, lights blazing, shipping enthusiastic passengers to the next site. Rising to a grey dawn on the sea’s face, geometric shaped grey islands on either side draw in colours. Santa Cruz fading into purple. Tortuga, a barren crescent of warm ochre. Isabela, by far the biggest island in the archipelago, shades of green and black. A new island ready to receive us with new adventures, new landscapes, different beasts, new waves to surf.